Newsletter Signup

The Austin Monitor thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Most Popular Stories

- City leaders evaluate surprising ideas for water conservation

- Audit: Economic official granted arts, music funding against city code

- Parks Board recommends vendor for Zilker Café, while voicing concerns about lack of local presence

- Dozens of city music grants stalled over missing final reports

- Council reaffirms its commitment to making Austin a more age-friendly city

-

Discover News By District

Popular Whispers

Sorry. No data so far.

What exactly is a Vision Zero plan? And why does Austin need one?

Monday, May 9, 2016 by Audrey McGlinchy, KUT

One hundred and two people died on Austin’s roads in 2015 – the most ever recorded. More than 20 have met a similar fate so far this year. Nearly every death involved a car. Yet, in a city where 93 percent of households own a car, Francis Reilly does not. Reilly works in the city’s Planning and Development Review Department.

“We acknowledge that everyone is going to make mistakes regardless of how you get around, but how do we design a system that prevents those mistakes from being fatal?” During a recent bus trip from his home in West Austin to his office on Barton Springs Road, Reilly talked through a yearlong project of the city: its Vision Zero plan.

The roughly 60 recommended actions in the plan – broken into five main sections: engineering, education, enforcement, policy and evaluation – map out the city’s attempt to eliminate deaths and serious injuries on Austin’s roads over the next two years. The city hopes to get to zero deaths by 2025. It’s the work of a 2014 City Council resolution, which created a task force of city and state staff, community advocates and academics.

But on a national scale, the Vision Zero concept is nothing new. Major cities like New York City and San Francisco have also adopted plans to accomplish this goal. While results in San Francisco remain to be seen, one year after lowering speed limits and implementing engineering changes and education campaigns in 2014, New York City saw its lowest number of pedestrian deaths in more than 100 years.

Vision Zero is much older than New York’s 2014 adoption of it. In 1997, the Swedish Parliament adopted the first-ever Vision Zero plan as countrywide policy.

Sweden’s Vision Zero plan focuses on street design. Intersections around the country are designed for pedestrians to safely cross short distances.

CREDIT MATTS-ÅKE BELIN

“In the traditional way that we work with safety, we focus very much on the individual road users,” says Matts-Ake Belin, with the Swedish Transport Agency. He was part of the team that founded the Vision Zero concept. But he explains that Vision Zero represents a cultural change in which people shift safety responsibility from drivers to engineers.

“We see this kind of mindset in other sectors of our society,” he says. “If you take, for example, safety work in a nuclear power station or in aviation, you will see that most of the thinking in these sectors is actually very similar to Vision Zero philosophy.” Apply that to the roads, says Belin.

“Ultimately, the responsibility for safety is on those who design the system.”

In other words, the road engineers.

Imagine a four-lane intersection, Belin says. The first instinct might be to install a traffic light. While the number of crashes will probably drop, Belin says, those few collisions will almost certainly be fatal.

“The typical scenario is that someone, by mistake, goes against this red light (at a) high speed into another car,” he says.

Instead, you might consider a roundabout.

Belin, with Sweden’s Transport Agency, says roundabouts can be a safer street design than traffic lights. Sweden created the first Vision Zero plan in the 1990s. Austin is working on its own plan to reduce traffic fatalities to zero by 2025.

CREDIT MATTS-ÅKE BELIN

“If you have a roundabout, the crashes might increase a little bit because it becomes a little bit more difficult for people to drive in a roundabout, but those (crashes) that will happen will be less severe,” he says. “(A) traffic light and a roundabout might actually be the difference between life and death.”

And that’s because a roundabout forces drivers to slow down. Speed, it turns out, lies at the heart of Sweden’s Vision Zero philosophy.

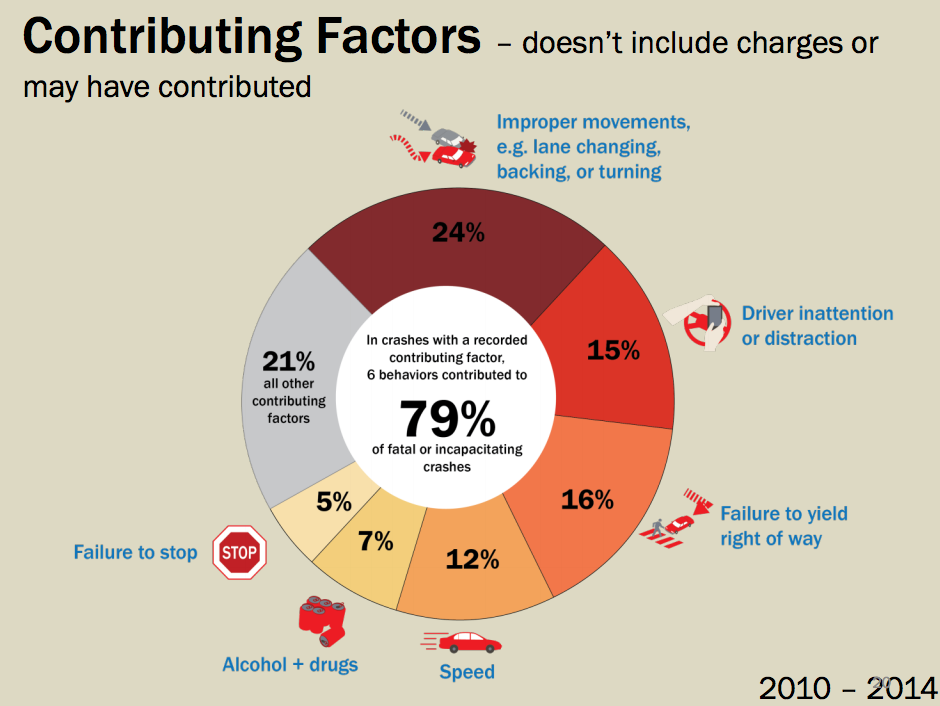

As Reilly explains, speed is one of six dangerous behaviors that contributed to last year’s record number of fatal crashes. Others include intoxication, failure to yield, failure to stop, distraction and improper maneuvers.

But are these behaviors changeable? And can the city’s Vision Zero recommendations shuttle it toward a mystical land of zero deaths or serious injuries on the road?

Belin says that because a Vision Zero policy accepts the premise that humans make mistakes on the road and they should not die as a result, much of the responsibility falls on engineers. A Vision Zero plan should be 90 percent engineering.

Sweden has cut its rate of traffic deaths in half (from seven deaths per every 100,000 people to three) since adopting a heavy engineering plan that includes building more roundabouts, installing physical barriers between lanes and reducing speed limits in urban areas.

According to the Vision Zero task force, these are the contributing factors of car crashes between 2010 and 2014. CREDIT CITY OF AUSTIN POWERPOINT

But in Austin, where eight out of every 100,000 people die on the road, the city’s Vision Zero plan is split evenly between education, enforcement and engineering.

City planners accept the premise that humans make mistakes.

“We acknowledge that everyone is going to make mistakes regardless of how you get around,” says Reilly. “But how do we design a system that prevents those mistakes from being fatal?”

Still, Austin’s Vision Zero plan also acknowledges that people must take responsibility for their own safety.

The question is: How should this responsibility be shared?

We’ll explore that in the rest of our Road to Zero series.

This is the first story in KUT’s series, The Road to Zero, which explores traffic deaths and injuries in Austin and the city’s plan to prevent them.

Top photo by GABRIEL CRISTÓVER PÉREZ/KUT NEWS

You're a community leader

And we’re honored you look to us for serious, in-depth news. You know a strong community needs local and dedicated watchdog reporting. We’re here for you and that won’t change. Now will you take the powerful next step and support our nonprofit news organization?